In 1943 Louis Untermeyer made a selection from the work of Robert Frost, and added a biographical introduction as well as running commentary on the poetry. The book, entitled Come In, was published by Henry Holt and Company….[ ] Now Mr. Untermeyer has extended Come In especially for Pocket Books, and the present volume contains 30 additional poems and a greatly enlarged commentary.

Most of the biographical information I present here comes from Mr. Untermeyer’s introduction on Robert Frost and his life (pgs. 1-14).

A Brief Frost Family History

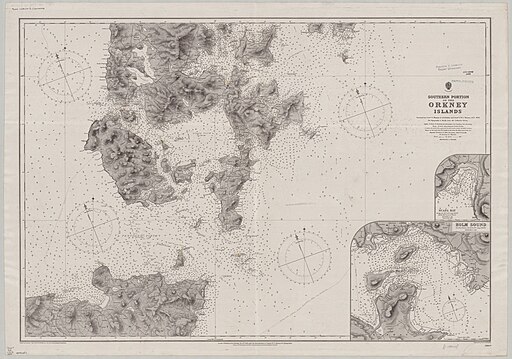

Robert Frost’s family first arrived in America in 1632. His ancestral family settled in New England. His mother, Isabelle Moodie, was Scottish of Orkneyan origin (meaning her family is from the Orkney Islands which are off the northern coast of Scotland). His father, William Prescott Frost, was of English origin (p. 3). It was William Frost, Robert’s father, who would break from his northeastern American roots, to begin a new, yet short lived, life in the West.

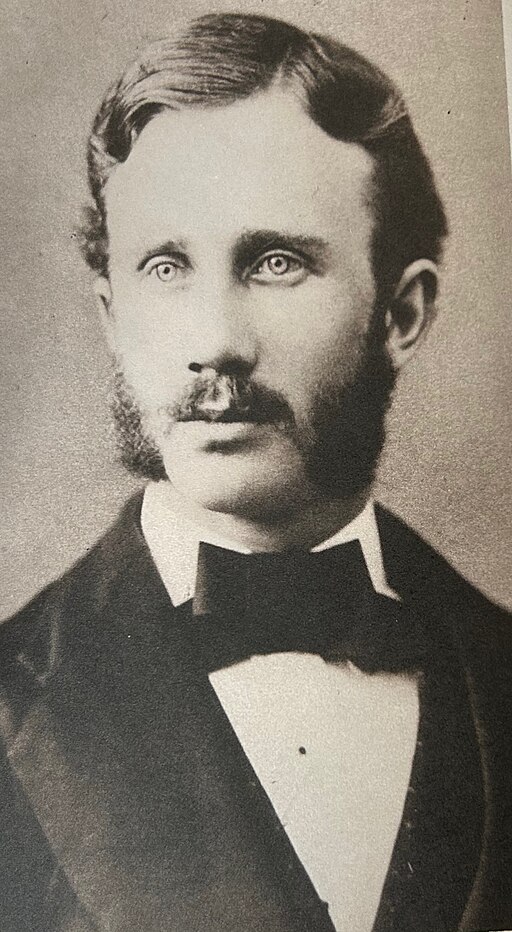

William P. Frost, Robert’s father, was the rebellious son. He disagreed with his family’s politics along with what his family had hoped he would become. His parents, Robert’s grandparents, wanted young William to be a lawyer, but that was not William’s aspiration. Instead, young William was drawn to writing, editing, and politics. At one time he made a failed ran for political office. Although, a generational northeasterner, he was frustrated with liberal minded New England, so in 1873, eight years after the end of the Civil war, he and Isabelle packed up and moved across the United States to San Francisco, California (p. 3).

Thoughts on the Father of the Poet

Untermeyer gives two paragraphs to Robert Frost’s father. Two paragraphs, seven sentences and 54 words. Yet, a lot is revealed about William Prescott Frost in those two paragraphs. Enough to lead me to wonder, had Robert’s father lived a long life, would we have the Robert Frost we know and admire today?

Dems vs. Reps pre-1940-Simplified

During the Civil War and up to the 1940s, the ideologies of America’s two main political parties were the opposite of what they are today. Republicans were considered to be more liberal leaning and wanted to abolish slavery. While Democrats were the conservatives that wanted to conserve states’ property rights; the right to keep humans as property- aka owning slaves.

New England was liberal Republican, as was the Frost family, except for William. He was what was a Copperhead (p.3). A southern sympathizer during the Civil War. Republicans created the term copperhead from the snake. A treasonous and untrustworthy person ready to stab you in the back at any moment. A really unfair comparison to the snake. It was meant to be a scathing insult. Yet many northern Democrats, like William, embraced the word with pride.

Racist papa? IMO

In my modern eyes, senior Frost was racist. A cross burning-lynching-violent type of racist? Doubtful. There’s no record of his involvement in such horrific activity. But, he was more racist than your average northerner.

As a side note: It’s naive to believe the totality of the white North, which was against slavery, was also for equal rights for people of color. There’s the ethics of slavery and there’s equal rights. For many northern Republicans the two topics were not from the same coin. Not seeing a person color of as equal to the same human rights as a white person is racist. Wanting to keep humans as property based on the color of their skin is also racism, but without compassion or humanity.

William Frost was from the Republican north (not to be confused with modern republicans), but he did not have the same beliefs nor ideologies of his northern neighbors or family. He was a proud copperhead. He never had slaves himself, but he believed that the cost of keeping human beings as slaves was worth keeping the Union together. Granted, I’m sure the word slaves meant property- so the argument would be, “a man has the right to own cows.” To justify slavery one has to see a slave as lesser then oneself, and in America, black people were lesser. In fact, they were not even considered full human. William was racist. Although, the word racist was not used during the time.

I’m inferring a lot from Untermeyer’s two paragraph’s, I know. This is my short story of William P. Frost: Due to his liberal leaning family and environment, William wanted to go to a place where he felt his views would be more accepted and appreciated. Going to the war ravaged and beaten south was out of the question. It was physically and economically destroyed and he wasn’t a “carpetbagger”. Frost needed to head somewhere new. He needed to manifest destiny to the west. The Wild West and the great western city, San Francisco. While there he worked as an editor for the Democratic newspaper the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, where he would freely express his opinions with like minded readers. Although, the Frosts had strong ancestral ties in New England, both Robert and his younger sister Jeanie were born in San Francisco.

This is not William’s Story

William Prescott Frost named his son Robert Lee Frost after the confederate General Robert E. Lee (p.3). Robert Frost the poet is named after a racist confederate general. Does it matter that W.P.F was a racist? Does it matter that our great American poet was named after a great racist general who happened to be good at war? I don’t think so. It is, however, interesting. It is history. It is a part of Robert Frost’s history, but it is not his story. His poems (at least the one’s I’ve read) never touched the on the subject of race or politics. I don’t know what was discussed over 100 years ago in the small household of the Frost family. Little Robert may or may not have absorbed some of his father’s beliefs. I don’t know, but we do know, factually, he never reached the age to talk to his father about those beliefs and ideologies because his father passed away when Robert was 10 (p.3).

Untermeyer did not elaborate on William’s ideologies. Like many writers of the era (1930s), he white washes over the fact that Robert was named after a racist Confederate General by calling him “the great southern general and scholar” (p.3). This Pocket Book series was published before the civil rights movement and during Jim Crow. History has context that’s understandable. However, context doesn’t doesn’t justify actions. It explains the choices behind an action, but rarely justifies certain choices. My guess is that during this time period it wasn’t controversial (in white circles) to admire a “great general” even if he did own human beings and fought for the right to keep them as cattle.

I want to make it clear that I am not saying that Robert Frost the poet had the same ideologies as his father, but it is a wild discovery to learn that his father, who was not a southerner, named his son after a confederate general. William Prescott Frost being a racist and devoted to the Confederacy enough to leave his own parents, doesn’t mean Robert Frost was the same. We can and often are influenced by our parents, but we are not our parents. After all, William did not align with his own parents’ beliefs. Robert may have disagreed with his father. As far as I know there is no account one way or the other.

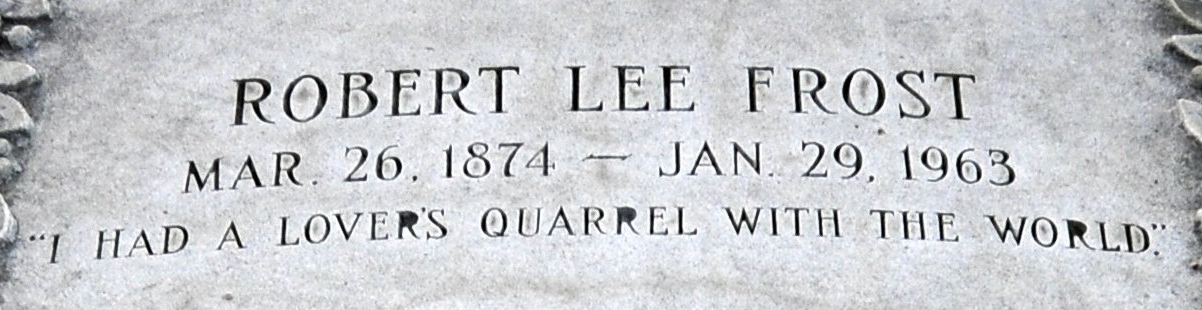

Robert Frost (1875-1963)

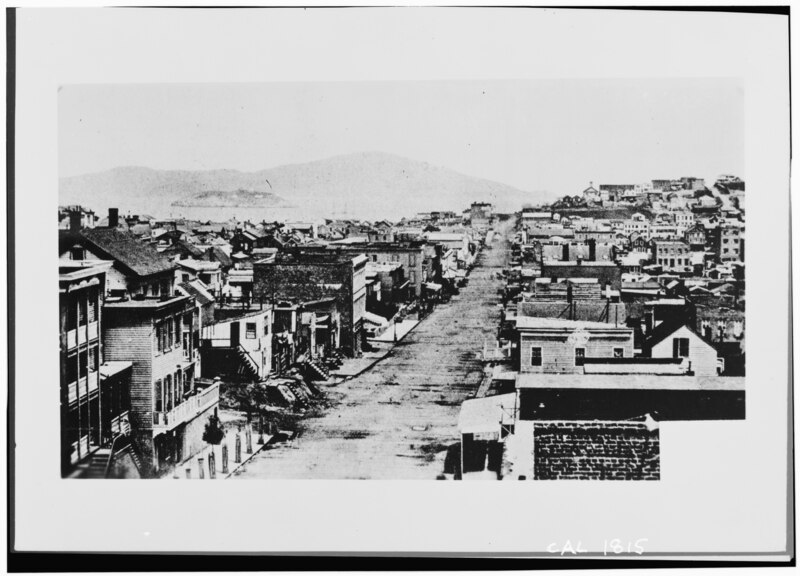

Born in the West

Robert was born in San Francisco during a wild and rough time. The city was booming and growing. It was the Wild West meets the Gilded Age. The Gold Rush opened the opportunity for anyone to get rich quick. There were new business opportunities and exciting new movements. The mansions of the Gilded Age threw shadows of disdain over the streets of the impoverished, and racism and anger over the ever growing Chinatown placed hardships and pain on the heads and shoulders of the Chinese population. William was said to have enjoyed the fast pace of the city. According to Untermeyer, William liked the rough parts of their life in San Francisco. It was dangerous at times, and William Frost loved the action (p.3). However, the city population was growing faster than the infrastructure. The lack of sanitation and overcrowding brought many diseases and William, in his early 30s, succumbed to one of the most prevalent killers of the time-tuberculosis.

After her husband’s death, broke and in mourning, Isabelle packed up the kids and left the west to return to their family home in New England.

One little discrepancy, according to Louis Untermeyer’s introduction, Robert Frost was born in 1875. However, the internet says Robert Frost was born in 1874. Robert Frost was alive when this book was published-and they were friends. Did Louis Untermeyer make a mistake? Did they miss it in the editing? After a little digging, I found a photograph of Frost’s headstone and the etched dates are March 26, 1874 to January 29, 1963. This leads me to believe the mistake is in the book.

Raised in the East

Isabelle, Robert’s mother, educated him. She taught him to read and through her he grew to love books. Yet, it was poetry that captured his heart. At the age of 14 he was reading many works, but was said to admired the writings of Poe and Emerson. He soon began writing his own poetry. He was 15 when his first poem was published in the Lawrence High School Bulletin. When he was 19 his poem was accepted by The Independent, a magazine with national circulation. He even received a $15 check for the poem. Although his mother was proud of him, the rest of his family, especially grandpa Frost, did not believe a poet could make a living. His grandfather told him that he would give Robert a year to become a poet, and Robert responded by saying, “Give me twenty” (p. 4).

Twenty-Five Years of Writing

His first book of poetry, A Boy’s Will, was published in 1913. It took him twenty-five years. He officially made it as a professional poet at the age of 38. This was only the beginning of his life as a working poet, but 25 years is a long time. What had he been doing during those years to keep his life afloat?

Beginning at age 12, Robert worked in shoe shops, on farms, and in a woolen mill (p. 5). He immersed himself in physical labor, but he also pursued his academic studies. He did his best to please his family through gaining an education, but Robert always knew he was going to be a poet.

He graduated as valedictorian from Lawrence High School. After high school he was accepted into Dartmouth, but he only attended the prestigious college for two months before returning home. In order to make a living, he took over one of his mother’s classrooms and began teaching at the age of 18. Three years after graduation he married the covaledictorian from his school, Elinor Miriam White (p. 4).

For the next few years Robert supported his family through teaching and editing for the Lawrence newspaper. Then at the age of 22, he decided to return to college, this time Harvard. Again, he left school early. Robert Frost never wanted to go to college. He had the academic chops for schools like Dartmouth and Harvard, but it wasn’t what he wanted to do. His attempts at college were all to please his family, in particular, his grandfather. Although, disappointed in his grandson, grandpa Frost gave young Robert and his wife a farm near Derry, New Hampshire (p. 6). Not to be confused with the Pennywise Derry, which we all know is in Maine.

The first farm

Robert worked the farm for ten years, which was the agreed terms he had set with his grandfather (p. 7). He wasn’t a farmer nor was Elinor his wife, but they learned to become farmers over time. It is something that they both took to (at least Robert did) as it was the first of many farms they would own and care for. Farm life didn’t pay for all of the bills, so Robert returned to teaching part of the time.

Robert was in his 30s and still not making a living as a poet, but he had never quit writing poetry. Elinor encouraged him to keep at it. They both had faith in his craft, but something needed to change. At the age of 35, and after the terms of the contract at the farm had ended, Robert sold the farm. Using the money from teaching and the sale of the farm, Robert, Elinor, and their children moved to England. This was the move that would change the lives of Robert and Elinor Frost forever.

Big in England

I’ve often said, America does not love its artists until they are already famous. America is the land of transaction. If you don’t offer something that can be given a price tag immediately then you aren’t worth a dime. Robert Frost did not become America’s poet until he left America.

Farming in England

England in 1912 was more affordable than the U.S. The Frost family moved to Buckinghamshire county in southeast England. They first settled into the rural village of Beaconsfield. There they kept themselves isolated from the town folks. According to Untermeyer, England was experiencing a literary revival, but Robert Frost took no part in the movement. I’m not even sure if he was aware of it at the time. After a year in Beaconsfield the family moved to Gloucestershire in southwest England and there they tried farming once again (p. 7).

It was in 1913, when Frost was going through some of his poetry, when he decided that perhaps, he would try and get a book of his poems published. In his words:

It came to me that maybe someone would publish a few of these poems in a book. It really hadn’t ever occurred to me before that this might be done. pg. 7

In 1913, at the age of 38, his first book, A Boy’s Will was published by David Nutt (actually his widow published the book). In 1914, David Nutt publishing published Frost’s second book, North of Boston. Life was going well in England until July of 1914 when their lives along with all of Europe were disrupted by WWI.

The Frosts returned to America, but instead of being an unknown farmer and school teacher, Robert returned as a famous poet. Both of his books, A Boy’s Will and North of Boston, were reprinted in the United States by Henry Holt and Company. The 40 year old Frost was considered the leader of “the new era in American poetry.” He was finally able to sustain his life and the life of his family on poetry. Sadly, his grandfather didn’t live long enough to see his grandson make a living as a poet. Robert bought another farm near Franconia, New Hampshire where he lived for 5 years writing poetry. Over the course of twenty years, Robert owned five farms, all in Vermont. He moved between these farms, and Boston and Cambridge as he continued to write books of poetry (p.10)

America’s Awarded Poet

Over the course of his literary life, Frost was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters at Harvard, the very same college that he dropped out of in his early 20s. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the best book of poetry four times. He was awarded honorary degrees from Columbia, Harvard, Dartmouth, Princeton, Oxford, Cambridge, and Bates college. Pretty good for a two time college dropout.

A lot Left Out

There is a lot I left out about Robert Frost like how he lost his mother and his first child in the same year. He outlived his wife and four of his six children. His family suffered from mental illnesses like schizophrenia and depression. His mother was institutionalized, along with his younger sister and one of his daughters. His son committed suicide. There was a lot of loss and tragedy in his life. A close read of some of his poems speak of grief and loss and moving on, but ultimately, what I read in Frost’s poems are a real love for the land, and for being alive to witness and experience life on this land. He shared his love of words, the soil, the work, and existence. He loved birds. We know this through his poetry. There are many poems to birds like Mary Oliver’s poems to dogs. How wonderful to express love for life through a poem. Lastly, he captured the life of rural America during the turn of the century. He captured an America that many still dream about; fresh air, water, soil, and nature. The time to work, the time to rest, and a time to reflect.

Reading Helps Writing

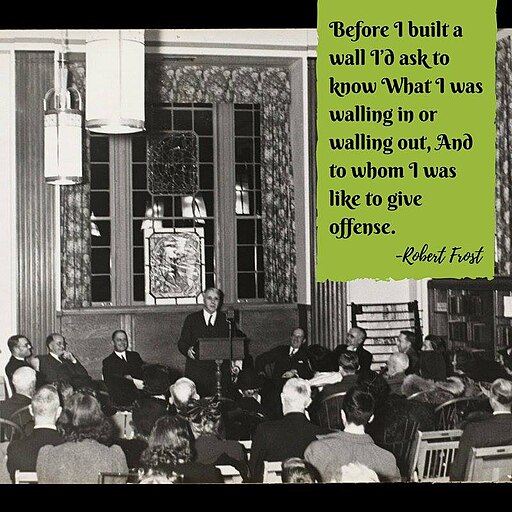

When a blank page looks intimidating, sometimes it helps me to explore the work of other poets. I’d like to continue exploring this Pocket Book of Poems.

In my future posts, I’ll be exploring the poetry itself. With many of Robert Frost’s poems now being in the public domain, I am free to print out many of his poems for a deeper analysis, which will be poemy-nerdy fun. Hopefully, some switch in my mind will flip, and a poem of my own will reveal itself to me.

Till then I’ll keep the porch light on.

Source:

Frost, Robert. The Pocket Book of Roberts Frost’s Poems. New York City, Pocket Book Inc, 1946. Introduction and Commentary by Louis Untermeyer, New York City, 1943, 1946.